Proprietary software is a barrier for African people to participate as equals in humanitarian and development work in their own continent. It helps perpetuate a monopoly on well-paid aid jobs enjoyed by people from wealthy, majority-white countries.

I’ve been working with colleagues in Tanzania to create elevation models for flood modeling using drone imagery. It’s an incredible project, and my Tanzanian colleagues are brilliant. However, there is an unexpected obstacle to the meaningful inclusion of my African colleagues, and to the project’s success:

Our European-based technical supervisor has demanded the use of proprietary software, despite the availability of free and open source software (FOSS) alternatives.

Our European supervisors are baffled as to why we object to this. They know that we want the highest quality output, just as they do. Why, then, would we be resistant to using “the best tools?” One of them wrote:

“I know you favour open source, but I would recommend [using X proprietary app]. The quality of the [FOSS function] is quite low compared to the [proprietary function]. As a consequence, you will need far more manual editing to clean up the [FOSS] result than you would need to clean up the [proprietary] result. For any serious project, I expect the costs for additional manual editing to be much higher than the costs for a [proprietary] license.”

This reflects a colossal misunderstanding of the African context. Our European colleagues on this project cost thousands of dollars per day[1]The cost of a European expert is not just salary; this includes institutional costs of their employers such as universities or consulting firms, which are often considerably more than the actual … Continue reading. The non-profit license for the proprietary application is $3,000. This represents a saving if it avoids as little as two days’ work by a European expert.

A brilliant, passionately motivated young Tanzanian professional costs on the order of $40/day (including institutional costs, and well above the median salary). The cost of this proprietary software license is equivalent to full funding for 3.5 working months of one of our African colleagues.

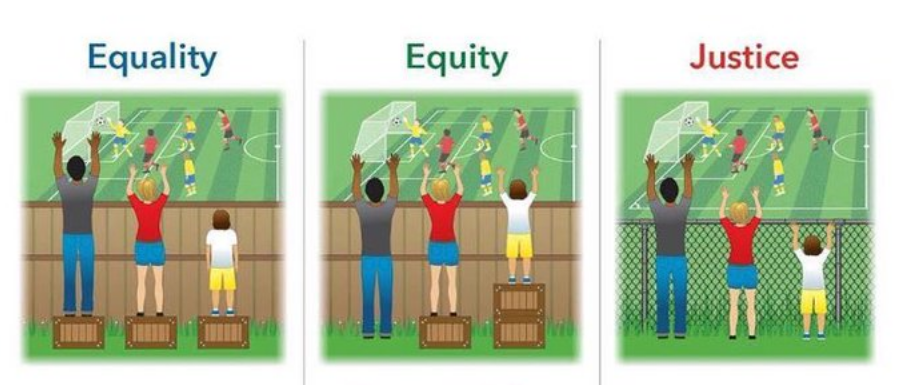

People from wealthy, majority-white countries cannot easily grasp the magnitude of the inequality that puts such tools out of reach for most African people.

A Tanzanian from a low-income family who is struggling to get through university will have almost no disposable income. And once they graduate with a master’s degree in a technical field, they can hope to receive a salary between $250 and $1,000 per month. A software package costing $3,000 might as well cost a million, for all that it’s practically available to them[2]Some tools may be licensed to their university, but most specialized ones are not—the proprietary tool used in the project I’m discussing here is fairly specialized, has a $2,000 educational … Continue reading.

Image source: (https://twitter.com/RaeHughart/status/1018310985164214273/photo/1)

Thus the African participant arrives on a project with absolutely no experience using the tools[3]A software license is often provided so that the African participants are able to use the software during the project. What they lack is the opportunity to work with it before and after the project … Continue reading [4]The use of “Cracked” proprietary software is widespread, even in professional settings. While this does result in a sort of access that allows people to develop skills, there are at least four … Continue reading, and the funding agency concludes that European experts are needed to do quality work on (to quote my colleague’s statement above) “any serious project” while African team members, who have less time to learn the tools, are seen as unqualified. This protects the ability of Western experts to continue consuming the lion’s share of development funds in Africa[5]This includes what is sometimes known as “circular aid”, whereby donor country funds ostensibly for poor people mostly get disbursed to citizens of that same wealthy donor country..

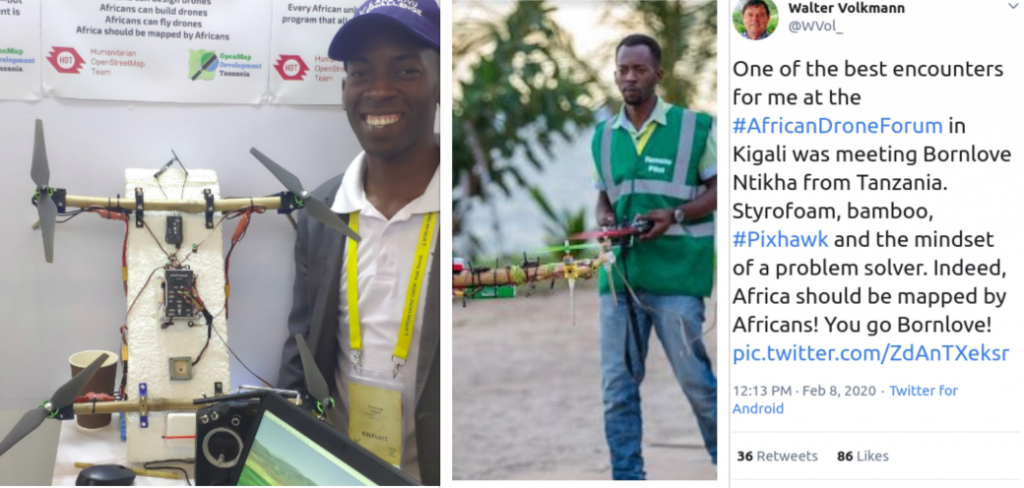

Tweet: https://twitter.com/WVol_/status/1226071618943930368

The use of proprietary products creates a vicious cycle whereby charitable and public development funds are effectively channeled to proprietary software companies, who improve their products[6]Or invest in their marketing and strategies to discourage the use of competing options. while FOSS developers struggle to find time and money, further widening the gap—and the barrier to entry[7] As a rule, the more a proprietary application in a technical field gains a quality edge over the free alternatives, the more their price goes up. Consumer-facing applications sometimes become … Continue reading, entrenching the Western monopoly on well-paid jobs in Africa.

What shall we do?

The entire development sector, from donors on down, should make the use of Free and Open Source Software tools whenever possible a default requirement.

- The use of proprietary tools should require specific justification based on urgent need, and explicitly not be budget-driven.

- “It’s cheaper because it’s faster” should not be considered a sufficient justification when the savings is predicated on massive salary disparities between Western and African workers.

- All required use[8]Please note we’re talking about situations where the contracting agency requires or encourages the use of proprietary software, either explicitly or implicitly. Mandating the use of a spreadsheet … Continue reading of proprietary software[9]Freeware, proprietary software monetized by ads, surveillance, or the expectation that some users will buy premium versions, has problems including privacy, the risk of data being locked in, and poor … Continue reading should include a mandatory, verifiable strategy to ensure that it is meaningfully available to local people (and not only those already employed in the relatively high-paying aid sector[10]African UN and World Bank employees can easily access proprietary software. They are, however, a small fraction of the African population, and often not from marginalized groups (it usually requires … Continue reading).

- For example, any proprietary software required by donors to execute projects should be made available freely (or at a cost proportionate to local incomes[11]If a software package costs $3000, that represents 6.7% of the median income in, for example, the Netherlands, where the average person earns $44,668 per year. In Tanzania, where the median annual … Continue reading) to local people and institutions wishing to bid on or participate in the work (this should include all those interested, not merely those shortlisted for contracts, and include students; the inequity is in access to gain the familiarity and skills to successfully bid on projects or get jobs, not access to required tools once contracted or funded). This would—in addition to reducing the tilt of the playing field—go some distance to revealing the true cost of proprietary software to the aid sector and society as a whole[12]A single donor-funded project requiring a proprietary software package may very well account for the cost of the purchase by the successful contractor. It does not account for the purchases by … Continue reading.

- If and when proprietary solutions are used despite the existence of FOSS alternatives, donors should provide grants to the maintainers of the alternatives to mitigate the market distortions arising from aid money funding their competitors[13]The Public Money Public Code movement advocates for the products of public funds to belong to the public; assets paid for by tax money shouldn’t be directly captured by private interests and … Continue reading.

- Donors should plan ahead; if a project requires a specific functionality that a FOSS product does not have, the cost of supporting its development should be factored into the decision whether to use a proprietary competitor to it. If the cost of developing a FOSS feature is within a visible distance of the cost of the proprietary application for a given project and is useful for other aid projects, basic fiduciary responsibility dictates that the FOSS alternative must be developed to avoid waste of aid funds by multiple projects buying the same proprietary product.

- If and when proprietary solutions are used despite the existence of FOSS alternatives, the resulting products (data, algorithms, and processes) should be made available using an open technology standard[14]Often proprietary products produce by default outputs that can only be read using proprietary software (and sometimes only by products from the same vendor). These proprietary formats block access … Continue reading, so that future projects can use and build upon the work using FOSS tools.

We can replace the vicious cycle of exclusion with a virtuous cycle of inclusion and human development. We work with FOSS tools, we invest in and share those tools, and more people can participate. More participation leads to better technical outcomes, a wider spread of knowledge, more reduction of poverty, and therefore more investment in those tools.

Anti-Racism in Aid Tech

The aid sector, both in the humanitarian and development sub-sectors, is increasingly aware of the racial inequities that pervade it. The aid sector must face its own inadequacies in light of the Black Lives Matter movement and philosophy. The technology niche within the humanitarian and development sector is even more steeped in white male privilege and exclusivity. The use of proprietary software amplifies and perpetuates this. We can—and should—stop using it.

Today, a Tanzanian colleague told me that since our team began emphasizing FOSS software several years ago, he has grown more skilled and more fully included as a participant in the global tech conversation. He specifically thinks this was made possible by the adoption of FOSS tools in the larger community around our team, in part due to our advocacy for those tools. The positive effects of making FOSS a priority are significant for individuals.

Much more work and fundamental change are necessary to remove the barriers to the meaningful inclusion of people of color—and break the monopoly of white Western people—in the aid sector. Lowering the barrier to technical work by using FOSS tools is a positive step that is well within our ability to implement now.

Thanks to the many friends who commented on or contributed to this essay, including Hawa Adinani, Iddy Chazua, William Evans, Chris Houston, Godfrey Kasano, Steve Mather, Freddie Mbuya, Dorica Mugusi, Immaculate Mwanja, Bornlove Ntikha, Kristen Tonga, Hassan Valji, and Hessel Winsemius. All errors are mine. Not all of the people listed here necessarily agree with everything said here; please blame me, not them.

References

| ↑1 | The cost of a European expert is not just salary; this includes institutional costs of their employers such as universities or consulting firms, which are often considerably more than the actual salaries |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Some tools may be licensed to their university, but most specialized ones are not—the proprietary tool used in the project I’m discussing here is fairly specialized, has a $2,000 educational license, and is not available in the Tanzanian universities my colleagues attended (or any others that I am aware of). |

| ↑3 | A software license is often provided so that the African participants are able to use the software during the project. What they lack is the opportunity to work with it before and after the project (it is almost invariably withdrawn or expires after the funding ends and the project concludes). |

| ↑4 | The use of “Cracked” proprietary software is widespread, even in professional settings. While this does result in a sort of access that allows people to develop skills, there are at least four problems with it: a) users of “cracks” are technically committing a crime in most jurisdictions (though many in Africa are not aware of this), b) it only works for popular applications; there are usually not “cracks” available for technical software in narrow specializations, c) the “cracked” software often doesn’t work right, and d) this helps entrench the proprietary application as fewer people use the legal FOSS alternatives. Speaking of the legality: if you believe that the use of “cracks” is justified or suggest it is how low-income people should learn, then either you don’t think using it is a crime (and therefore you don’t really believe in proprietary software, welcome aboard), or you think that the inequitable access justifies this crime (in which case read on; there is a better solution)! |

| ↑5 | This includes what is sometimes known as “circular aid”, whereby donor country funds ostensibly for poor people mostly get disbursed to citizens of that same wealthy donor country. |

| ↑6 | Or invest in their marketing and strategies to discourage the use of competing options. |

| ↑7 | As a rule, the more a proprietary application in a technical field gains a quality edge over the free alternatives, the more their price goes up. Consumer-facing applications sometimes become more affordable as companies attempt to attract a larger user base, but this rarely happens with technical packages that have a small set of potential users and therefore relatively inelastic demand. There’s no incentive to lower the price unless it would attract more users. |

| ↑8 | Please note we’re talking about situations where the contracting agency requires or encourages the use of proprietary software, either explicitly or implicitly. Mandating the use of a spreadsheet is fine, provided it doesn’t specify if it should be Microsoft Excel or LibreOffice Calc and doesn’t explicitly make the use of exclusive features of Excel necessary (there are a few Excel functions, particularly around macros, that don’t work in LibreOffice, but the overwhelming bulk of Excel’s functionality is present, and files can usually be seamlessly passed between the two systems). |

| ↑9 | Freeware, proprietary software monetized by ads, surveillance, or the expectation that some users will buy premium versions, has problems including privacy, the risk of data being locked in, and poor functionality in low-income settings due to bandwidth requirements. However, it doesn’t contribute much to the problem we’re discussing here: a barrier to access that perpetuates a monopoly on well-paid jobs. Therefore for the purposes of the current discussion we are not suggesting eliminating the use of Freeware (there are other reasons to consider this, but that’s for another time). |

| ↑10 | African UN and World Bank employees can easily access proprietary software. They are, however, a small fraction of the African population, and often not from marginalized groups (it usually requires substantial resources to acquire the credentials and connections needed to land such jobs). Genuine inclusion reaches beyond those who already have highly-paid internationally-funded positions. |

| ↑11 | If a software package costs $3000, that represents 6.7% of the median income in, for example, the Netherlands, where the average person earns $44,668 per year. In Tanzania, where the median annual income is $848, this software is 353% of the median income; the average person would have to refrain from spending a penny on food, shelter, or other items for 3.5 years in order to purchase it. To provide equitable access based on median income, the price in Tanzania should be $56.95, and would, therefore, require a discount or subsidy of $2,943 per purchase. Median income from the World Bank. |

| ↑12 | A single donor-funded project requiring a proprietary software package may very well account for the cost of the purchase by the successful contractor. It does not account for the purchases by unsuccessful bidders, or those by students and job seekers who need to be up to speed with the required tools before they can even enter the market. The aid sector as a whole pays many more times for proprietary software than just the licenses used on projects. This doesn’t even begin to account for the opportunity cost to beneficiary societies of bright, motivated local people not participating in the market at all because they can’t get onto the first rung of the ladder. |

| ↑13 | The Public Money Public Code movement advocates for the products of public funds to belong to the public; assets paid for by tax money shouldn’t be directly captured by private interests and withheld from the public that paid for them. Since a lot of aid money is public, and in any case should help beneficiary societies in the broadest way possible, a similar principle should apply. |

| ↑14 | Often proprietary products produce by default outputs that can only be read using proprietary software (and sometimes only by products from the same vendor). These proprietary formats block access not only to the tools, but also to the results and therefore much of the benefit of aid work. |